By Mr. James Burchill and Ms. Meghann Murphy

On June 7, 2012, the Center for Technology and National Security Policy (CTNSP) hosted an event on the Hill for the United States House Subcommittee for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) on Cyber-security, Infrastructure Protection, and Security Technologies on severe solar storms and national critical infrastructure.

The event was organized by Dr. Alenka Brown, Mr. James Burchill, and Ms. Meghann Murphy, from the National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for Technology and National Security Policy.

Panel participants included: Mr. Scott Pugh of Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Mr. Bill Murtagh of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Colonel Daniel Edwards of the United States Air Force (USAF), and Dr. Alenka Brown of NDU.

Congressman Dan Lungren, Chairman of the Subcommittee, wanted his subcommittee members to become educated in two areas: 1) solar storms and the impact of these storms on US critical infrastructures, and 2) the difference between a severe geomagnetic storm and an electrical magnetic pulse. The request to CTNSP was based on two October exercises that CTNSP/NWC conducted between Oct. 3 and 5, 2012. These exercises were conducted to address the possibility of a severe solar storm, similar to the Carrington Event of 1859 (one of the largest solar storms to be recorded in US history), and the possible effects to the US national grid prompted by such a solar storm.

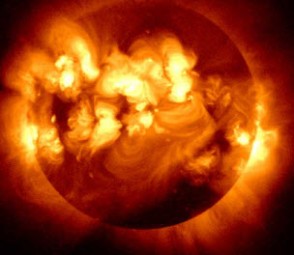

We know that geomagnetic storms are caused by fluctuations in the Sun’s magnetic field, and these often occur in growing frequency within an eleven year cycle known as the solar maximum. We are currently approaching its zenith. This is of concern as sufficiently large geomagnetic storms can cause numerous issues to critical infrastructure. Satellite operations and communications can be disrupted throughout the storm which can last many hours. Potentially longer term effects can be seen in the disruption of the electrical grid, e.g., high-voltage transformers which are critical to operation of our long distance transmission lines and large power plants.

The panelists were to educate the subcommittee members and senior professional staffers on the basics of geomagnetic storms and the effects on US critical infrastructures. The audience consisted of Congresswoman Richardson, and senior professional and junior staffers. Chairman Lungren apologized for his absence and those of his other colleagues due to an unexpected classified briefing.

The panelists began by discussing the underlying science concerning solar storms given by Mr. William Murtagh, NOAA. Mr. Scott Pugh, DHS, followed with an explanation of the difference between a severe solar storm and electric magnetic pulse. He walked the audience through a severe geomagnetic storm exercise describing possibly consequences to our critical infrastructure based on a severe outage of the national electrical grid. Dr. Alenka Brown, NDU, spoke on cascading effects should a solar storm occur, with emphasis on the population, the financial sector, and cyber. Colonel Daniel Edwards, United States Air Force, Space Weather Group, gave a brief on how the military might engage during a solar storm event.

The outcome was a follow up future event that would provide a more in-depth analysis of severe geomagnetic storms in relationship to the US critical infrastructures to the subcommittee members. It was proposed that the National Defense University in collaboration with the Department of Homeland Defense would host the event. In addition, a one-pager has been written and will be sent to the key panelist and Congressman Dan Lungren’s office.

You must be logged in to post a comment.